|

Marzo 1521

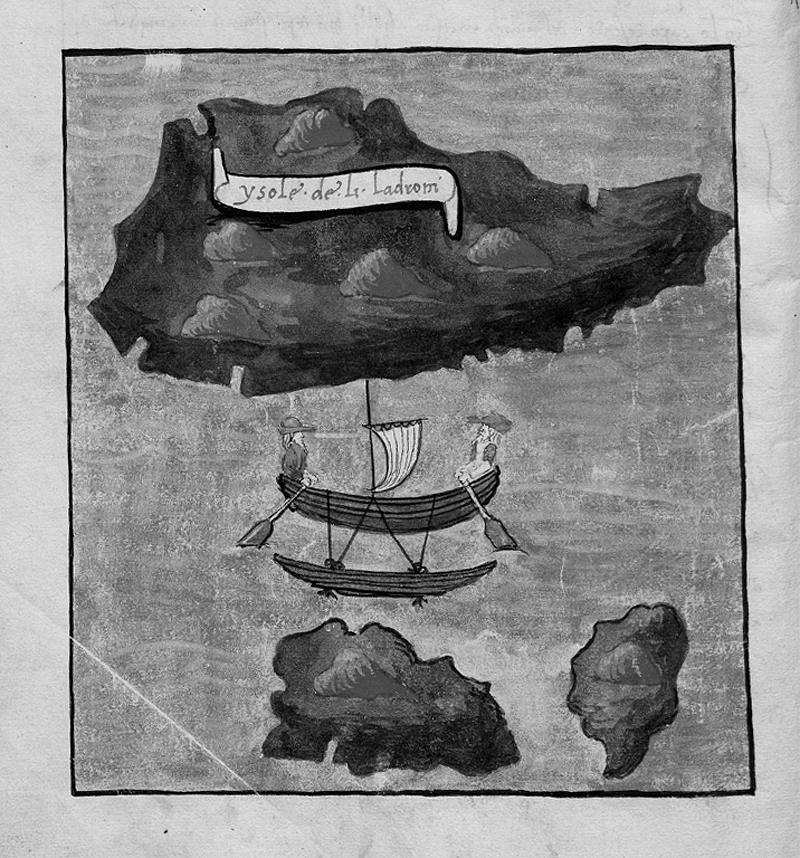

Circa de setanta legue a la detta via in dodeci gradi di latitudine et 146 de longitudine Mercore a 6 de marso discopressemo vna ysola aL maistralle picola et due alte aL garbino vna era piu alta et piu granda de Laltre due iL capo generale voleua firmarse nella grande þ pigliare qalque refrigerio ma nō puote perche la gente de questa Jzolla entrauano nele naui et robauano qi vna cosa qi lalta talmente ɋ non poteuamo gardarsi. Voleuano calare le vele acio andasemo in tera ne roborono lo squifo ɋ estaua ligato a La popa de la naue capa cō grandissa presteza þ il que corozato eL capo generalle ando in tera con Quaranta huomini armati et bruzarono da quaranta o cinquanta caze cō molti barquiti et amazorono sette huomini et rehebe lo squifo Subito ne parti semo sequendo Lo medesimo camino. Jnanzi ɋ dismontasemo in tera alguni nosti infermi ne pregorono se amazauamo huomo o donna li portasemo Ly interiori þ che Subito sarebenno sani.

Quando feriuamo alguni de questi cō li veretuni ɋ li passauano li fianqi da luna banda alaltra tirauano il veretone mo diqua mo diLa gardandoLo poi Lo tirauano fuora marauigliandose molto et cussi moriuano et alti ɋ erano feriti neL peto faceuano eL Simille ne mosseno agrā compasione Costoro vedendōe partire ne seguitorono cō piu de Cento barchiti piu de vna legua Se acostauano ale naui mosstrandone pesce cō simulatiōe de darnello ma traheuano saxi et poi fugiuano andando le naue cō velle piene pasa vano fra loro et li batelli con qelli sui barcheti molto destrissimi vedesemo algune femine in li barqueti gridare et scapigliarse credo þ amore de li Suoi morti.

Ognuno de questi vive secondo la Sua volonta non anno signori vano nudi et alguni barbati con li capeli negri fino a lo cinta ingropati portano capeleti de palma como li albanezi sonno grandi como nui et ben disposti nō adorāo niente sonno aliuastri ma nascono bianqi anno li denti rossi et negri þ che la reputano belissima cosa le femine vano nude senon ɋ dinanzi a la sua natura portano vna scorsa streta sotille come la carta ɋ nasce fra larbore et la scorza de la palma sonno belle delicate et bianque piu que li huomini cō li capilli sparsi et longui negrissimi fino in tera Queste nō lauorano ma stanno in casa tessendo store casse de palma et altre cose necessarie acasa sua mangiano cochi batate vcceli figui longui vno palmo canne dolci et pesci volatori cō altre cose se ongieno eL corpo et li capili cō oleo de cocho et de giongioli le sue case tute sonno facte di legnio coperte de taule cō foglie defigaro de sopa longue due braza con solari et cō fenestre li camare et li lecti tucti forniti di store belissime de palma dormeno soura paglia di palma molto mole et menuta nō anno arme Senon certe aste cō vno osso pontino de pesce ne La cima Questa gente e pouera ma ingeniosa et molto ladra þ questo chiamassemo queste tre Jsole le ysole de li ladroni eL suo spaso e andare cō Le donne þ mare cō qelle sue barquete Sono como le fucelere ma piu strecti alguni negri bianqi et alti rossi anno da lalta parte dela vella vno legno grosso pontino nele cime cō pali atrauersadi qeL sustentano neL acqua þ andare piu seguri aLa vela la vela e di foglie de palma cosite insieme et facta amodo de latina þ timone anno certe pale como da for no cō vno legnio in cima fanno de la popa proua et de la proua popa et sonno Como delfini saltar a lacqua de onda in onda Questi ladroni pensauano ali segni ɋ faceuāo nō fusero alti homini aL mondo senon loro.

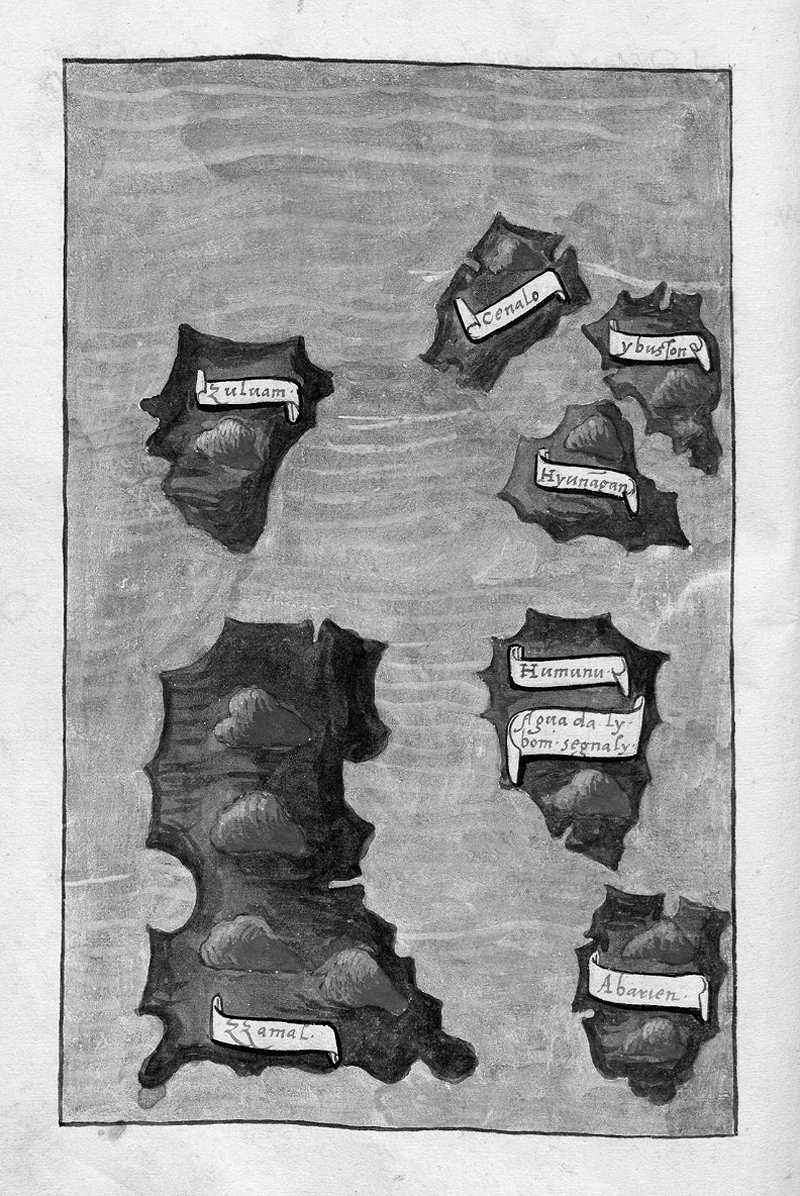

Sabato a sedize de marso 1521 dessemo neLa aurora soura vna tera alta lōgi trecento legue delle ysolle de li latroni laqaL e ysola et se chiama Zamal eL capo gñale nel giorno seguente volse dismontare in vnalta ysola deshabitata þ essere piu seguro ɋ era di dietro de questa þ pigliare hacqua et qalque diporto fece fare due tende in terra þ li infermi et feceli amazare vna porcha Luni a 18. de marso vedessemo dapoi disnare venire verso de nui vna barca cō noue homini þ ilque lo capo generale comando ɋ niuno Si mouesse ne dicesse parolla alguna senza sua lisentia Quando ariuorono questi in terra subito Lo suo principalle ando aL capo gñale mostrandose alegro þ la nȓa venuta restarono cinqƺ de questi piu ornati cō nuy li alti andorono a leuare alguni alti ɋ pescauano et cussi venirono tucti vedendo Lo capo gñale que questi erano homini cō ragionne li fece dare da mangiare et li donno bonneti rossi spequi petini sonagli Auorio bocassini et alte cose Quando vistenno la cortesia deL capo li presentorono pesci vno vaso de vino de palma ɋ Lo chiamano Vraca figui piu longui dun palmo et altri piu picoli piu saporiti et dui cochi alhora nō haueuano alto ne fecoro segni cō La mano ɋ in fino aquatro giorni portarebenno vmay ɋ e riso cochi et molta altra victuuaglia.

Li coqi sonno fructi deLa palma cosi como nui hauemo iL panne iL vino lo oleo et lacetto cosi anno questi populi ogni cosa da questi arbori anno eL vino in questo modo forano La dicta palma in cima neL coresino de to palmito dalqalle stilla vna lichore como e mosto biancho dolce ma vn pocho brusqueto in canne grosse come La gamba et piu latacano alarboȓ la sera þ la matina et la matina þ la sera Questa palma fa vno fructo iL qalle he lo cocho Questo cocho e grande como iL capo et piu et meno La sua pima scorsa e þde et grossa piu de dui diti nelaqalle trouano Certi filittj ɋ fanno le corde ɋ liganno le sue barque soto di questa ne he vna dura et molto piu grossa di quella de la noce questa la brusano et fano poluere bonna þ loro soto di questo e vna medola biancha grossa come vn dito LaqaL mangiano fresca cō La carne et pessi como nui lo panne et de qeL sapore ɋ he la mandola qui la secasse se farebe panne in mezo di questa medola e vna hacqua quiara dolce et molto cordialle et quando questa hacqua sta vn pocho acolta se congella et diuenta como vno pomo Quando voleno fare oglio piglianno questo cocho et lassano putrefare qella medola cō lacqua et poi la fanno buglire et vene oleo como butiro Quando voleno far aceto lasanno putrefare lacqua solamente poi lameteno aL solle et e aceto como de vino biancho si po fare ancho latte como nui faceuamo gratauamo qƺsta medola poi la misquiauamo cō lacqua sua medesima strucandola in vno panno et cosi era late como di capra. Queste palme sonno como palme deli datali ma non cosi nodose se non lisce. Vna famiglia de x personne cō dui de queste se manteneno fruando octo giorni luna et octo giorni La alta þ Lo vino þ che se altramenti facesseno Se secharebenno et durano cento anny.

Grande familliaritade pigliarono cō nui Questi populi ne discero molte cose como le chiamauano et li nomi de algune ysole ɋ se vedeuano de qi La sua se chiama Zuluan laqalle non etropo grande pigliascemo grā piacere cā questi perche eranno asay piaceuoli et conuersabili iL capo gñale þ farli piu honnore li meno ala sua naue et li mostro tuta la sua mercadansia garofoli cannella peuere gengero nosce moscade Matia oro et tute le cose ɋ eranno nella naue fece descaricare algune bombarde hebero grā paura et volsero saltar fuora de la naue ne fecero segni que li doue nuj andauamo nascesseuano cose Ja dete Quando si volsero partire pigliarono lisentia con molta gratia et gentileza dicendo ɋ tornarebeno segondo la sua þmessa La ysola doue eramo se chiama humunu ma noy þ trouarli due fondana de hacqua chiarissima la chiamessemo lacquada dali buoni se gnialli þ che fu iL pimo segnio de oro ɋ trouassemo in questa parte. Qiui si troua grā cantitade de coralli biancho et arbori grandi ɋ fanno fructi pocho menori de La mandola et sonno Como li pignioli et ancho molte palme algune bonne et algune altre catiue in Questo Locho sonno molte ysole. þ ilque Lo chiamassemo larcipelago de s. lazaro descourendo lo nella sua dominicha iL quale sta in x gradi de latitudine aL polo articho et Cento e sesanta vno di longitudine della linea deLa repartitiōe.

Vennere a 22 de marzo venirono in mezo di qelli homini Secondo ne haueuano þmesso in due barcque cō cochi naransi dolci vno vaso de vino de palma et vno galo þ dimostrare que in queste parte eranno galine se mostrarono molto alegri verso de noi comprassemo tute qelle sue cose iL suo sor era vechio et de pinto portaua due Schione de oro a le oreqie li altri molte maniglie de oro ali brazi cō fazoli in torno Lo capo Stesemo quiui octo [giorni] neliqalli eL nȓo capo andaua ogni di in terra auisitare ly infirmi et ogni matina li daua cō le sue mani acqua deL cocho ɋ molto li confortaua di dietro de questa ysola stanno homini ɋ anno tanto grandi li picheti de Lorechie ɋ portanno le braci ficati in loro Questi popoli sonno caphri çioe gentili vanno nudi cō tella de scorsa darbore intorno le sue vergonie se nō alguni principali cō telle de banbazo lauorate neli capi cō seda aguchia sonno oliuasti grassi de pinti et se ongeno cō olio de cocho et de giongioli þ lo solle et þ iL vento anno li capili negrissimi fina a La cinta et anno dague cortelli lanse fornite de oro targoni facine arponi et rete da pescare come Rizali le sue barche sonno corno le noste

NeL luni sancto a vinticinqƺ de marso giorno de La nȓa donna passato mezo di essendo de hora in ora þ leuarsi anday abordo de la naue þ pescare et metendo li piedi sopra vna antena þ descedere nela mesa degarni tiōe me slizegarono þ che era piouesto et cosi castai neL mare ɋ ninguno me viste et essendo quasi sumerso me venne ne La mano Sinistra La scota de La vella magiore ɋ era ascosa ne lacqua me teni forte et Comensai agridare tanto ɋ fui ajutato cō Lo batelo nō credo Ja per mey meriti ma þ la misericordia di qella fonte de pieta fosse ajutato. neL medesimo Jorno pigliassemo tra iL ponente et garbĩ infra quato ysolle çioe Cenalo hiunanghan Jbusson et abarien

Joue a vinti octo de marzo þ hauere visto la nocte passata fuocho in vna ysola ne la matina surgissemo apresso de questa vedesemo vna barcha picola ɋ la chiamano boloto cō octo nomini de dento aþpincarse nela naue Ca pitanea Vno schiauo deL capo gñale ɋ era de zamatra gia chiamata traprobana li parlo ilqalle subito inteseno venero neL bordo de la naue nō volendo intrare dento, ma stauano vno pocho discosti vedendo eL capo ɋ nō voleuano fidarsi de nui li buto vn bonnet rosso et altre cose ligate supa vn pezo de taula La piglioronno molto alegri et Subito Se partirono þ auisare el suo re deli circa due hore vedessemo vegnire due balanghai sonno barche grande et cusse le chiamano pienni de huomini neL magioȓ era Lo suo re Sedendo soto vno coperto de store Quando eL giunse apsso La capitania iL Schiauo li parlo iL re lo intese þ che in queste parte li re sanno piu linguagij ɋ li alti comando ɋ alguni soi intrasseno nele naue luy sempre stete neL suo balanghai poco longi de La naue fin che li suoi tornoronno et subito tornati se parti. iL Capo gñalle fece grande honnore aqelli ɋ venirono nela naue et donnoli algune cose per ilche il re inanzi la sua partita volse donnare aL capo vna bava de oro grande et vna sporta piena de gengero ma luj rengratiandoL molto nō volce acceptarle neL tardi andasemo cō le naue apresso la habitatiōe deL re.

JL giorno seguente ɋ era eL venerdi sancto eL capo gñale mando lo squia ua ɋ era lo interprete nȓo in tera in vno batello adire aL re se haueua alguna cosa da mangiare la facesse portaȓ in naue ɋ restariano bene satisfati da noi et como amici et nō Como nimici era venuti a lasua ysola eL re venne cō sey vero octo homini neL medesimo batello et entro nela naue abrazandosi col capo gñale et donoli tre vazi di porcelanna coperti de foglie pienne de rizo crudo et due orade molto grande cō altre cose eL capo dete al re vna veste de panno rosso et giallo fato a La torchesca et vno bonnet rosso fino ali alti Sui aqi cortelli et aqi specqi poy le fece dare la Colatiōe et þ il chiauo li fece dire ɋ voleua essere cun lui casi casi cioe fratello rispose ɋ cossi voleua essere verso de lui dapoy lo capo ge mostro panno de diversi colori tela corali et molta alta mercantia et tuta lartigliaria facendola descargare alguni molto si spauentorno poi fece armare vno homo cō vno homo darme et li messe atorno tre cō spade et pugniale ɋ li dauano þ tuto iL corpo þ laqaL cosa eL re resto casi fora dise li disse þ il Schiauo ɋ vno de questi armati valeua þ cento de li suoi respose ɋ era cussi et ɋ in ogni naue ne menaua duzento ɋ se armauano de qella sorte li mostro Corazine spade et rodelle et fece fare a vno vna leuata poi Lo condusse supa la tolda dela naue ɋ he in cima de la popa et fece portare la sua carta de nauigare et La bussola et li disse þ linterprete como trouo Lo streto þ vegnire alui et Quante lune sonno stati senza vedere terra Se marauiglio in vltimo li disce ɋ voleua se li piacesse mandare seco dui homini acio li mostrasse algune de le sue cose respose ɋ era contento yo ge anday cō vno alto

Quando fui in tera il re leuo le mani aL ciello et poi se volta conta nuy dui facessemo lo simille verso de lui cosi tuti li alti fecero il re me piglio þ La mano vno suo principale piglio lalto compago et cussi ne menorō soto vno coperto de cane doue era vno balanghai longo octanta palmi deli mey Simille a vna fusta ne sedessemo sopa la popa de questo sempre parlando con segni li suoi ne stauano in piedi atorno atorno cō spade dague Lanze et targoni fece portare vno piato de carne de porco cō vño vazo grande pienno de vino beueuamo adogni boconne vna tassa de vino lo vino ɋ li auansaua qalque volta ben ɋ fosceno poche se meteua in vno vazo da þ si la sua tasa sempre staua coperta ninguno alto li beueua Se nō il re et yo Jnanzi ɋ lo re pigliasse la tassa þ bere alzaua li mani giunte al çielo et verso de nui et Quando voleua bere extendeua lo pugnio dela mano sini stra verso dime prima pensaua me volesse dare vn pognio et poi beueua faceua cosi yo verso il re Questi segni fanno tuti luno verso de Laltro quando beueno cō queste cerimonie et alti segni de amisitia merenda semo mangiay neL vennere sancto carne þ nō potere fare alto Jnanzi ɋ venisse lora de cenare donay molte cose al re ɋ haueua portati scrisse asai cosse como le chiamanāo Quanto Lo re et li alti me vistenno fcriuere et li diceua qelle sue parolle tutti restorono atoniti in questo mezo venne lora de cenare portoronno duy plati grandi de porcelanna vno pienno de rizo et lalto de carne de porcho cō suo brodo cenassemo cō li medesimj segni et cerimonie poi andassemo aL palatio deL re eLqalle era facto como vna teza da fienno coperto de foglie de figaro et de palma era edificato soura legni grossi alti de terra qeL se conuiene andare cō scalle ne fece sedere sopa vna stora de canne tenendo le gambe atracte como li Sarti deli ameza ora fo portato vno piato de pesce brustolato in pezi et gengero þ alora colto et vino eL figliolo magiore deL re chera iL principe vene doue eramo il re li disse ɋ sedesse apresso noi et cossi sedete fu portato dui piati vno de pesce cō lo sue brodo et lalto de rizo acio ɋ mangiassemo col principe il nȓo compago p tanto bere et mangiare diuento briaco Vzano þ lume goma de arbore ɋ la quiamāo anime voltata in foglie de palma o de figaro el re ne fece segno qeL voleua andare adormire lasso cō nui lo principe cō qalle dormisemo sopa vna stora de canne cō cossini de foglie venuto lo giorno eL re venne et me piglio þ La mano cossi andassemo doue aveuamo cenato þ fare colatiōe ma iL batelle ne venne aleuare Jnanzi la partita eL re molto alegro ne baso le mani et noi le sue venne cō nui vno suo fratello re dunalta ysola cō tre homini Lo capo gñale lo retenete adisnare cō nui et donoli molte cose.

Nella ysola de questo re que condussi ale naui se troua pezi de oro grandi como noce et oui criuelando la terra tutti li vaso de questo re sonno de oro et anche alguna parte de dela casa sua cosi ne referite Lo medesimo re se gondo lo sue costume era molto in ordine et Lo piu bello huomo que vedessemo fra questi populi haueua li capili negrissimi fin alle spalle cō vno velo de seta sopa Lo capo et due squione grande de horo tacatte ale orechie portaua vno panno de bombazo tuto Lauorato de seta ɋ copriua dala cinta fino aL ginoquio aL lato vna daga cō Lo manicho al canto longo tuto de oro iL fodro era de legnio lauorato in ogni dente haueua tre machie doro ɋ pareuano fosseno ligati cō oro oleua de storac et beligioui era oliuastro et tuto depinto. Questa sua ysola se chiama butuan et calagan. Quando questi re se voleuano vedere ve neno tuti due aLa caza in questa ysola doue eramo eL re pimo se qiama raia colambu iL segundo raia siaui.

Domenicha vltimo de marso giorno de pasca nela matina þ tempo eL capo gñale mando il prete cō alcanti aparechiare þ douere dire messa cō lo interprete a dire al re ɋ nō voleuamo discendere in terra þ disinar secho ma þ aldire messa þ ilque Lo re ne mando dui porqi morti Quando fu hora de messa andassemo in terra forse cinquanta huomini nō armati la verso na ma cō le altre nȓe arme et meglio vestite ɋ potessemo Jnanzi que aruassemo aLa riua cō li bateli forenno scaricati sej pezi de bombarde in segnio de pace saltassemo in terra li dui re abrassarono lo capo gñale et Lo messeno in mezo de loro andassemo in ordinanza fino aL locho consacrato non molto longi de la riua Jnanzi se comensasse la messa iL capo bagno tuto eL corpo de li dui re con hacqua mosta da Se oferse ala messa li re andorono abassiare la croce como nuy ma nō oferseno Quando se leuaua lo corpo de nȓo sor stauano in genoquioni et adorauanlo cō le mane gionte le naue tirarono tuta La artigliaria in vno tempo quando se leuo Lo corpo de xo dando ge Lo segnio de la tera cō li schiopetj finita la messa alquanti deli nosti se comunicorono Lo capo generale fece fare vno ballo cō le spade deque le re hebenno grā piacere poi fece portare vna croce cō li quiodi et la coronna alaqaL subito fecero reuerentia li disse per Lo interprete como questo era iL vessilo datoli daLo inperatoȓ suo signore açio in ogni parte doue andasse metesse questo suo segnialle et che voleua meterlo iui þ sua vtilita þ che se venesseno algune naue dele nȓe saperianno cō questa croce noj essere stati in questo locho et nō farebenno despiacere aloro ne ale cose [cose: doublet in original MS.] et se pigliasseno alguno de li soi subito mostrandoli questo segnialle le lasserianno andare et ɋ conueniua meteȓ questa croce in cima deL piu alto monte que fosse açio vedendola ogni matina La adorasseno et seqƺsto faceuano ne troui ne fulmini ni tempesta li nocerebe in cosa alguna lo ringratiorno molto et ɋ farebenno ogni cosa volentieri ancho li fece dire se eranno morj ho gentili o inque credeuāo risposero ɋ nō adorauāo alto sinon alsauano le mani giunti et la faza al ciello et ɋ chiamauāo Lo sua dio Abba þ laqaL cosa lo capo hebe grande alegressa vedendo questo eL pimo re leuo le mani aL ciello et disse ɋ voria se fosse possibille farli vedeȓ iL suo amore verso de lui Lo interprete ge disse þ qaL cagiōe haueua quiui cosi pocho da mangiare respose ɋ nō habitaua in qƺsto Locho se nō quādo veniua a La caza et a vedere Lo suo fratello ma staua in vna alta ysola doue haueua tuta la sua famiglia li fece dire se haueua Jnimici Lo dicesse þ cio andarebe cō queste naue adestrugerli et faria lo hobedirianno Lo rengratio et disse ɋ haueua benne due ysolle nemiche maque alhora nō era tempo de andarui Lo Capo li disse se dio facesse ɋ vnalta fiatta ritornasce in queste parte conduria tanta gente ɋ farebe þ forsa eserli sugette et que voleua andare adisnare et dapoy tornarebe þ far pore la croce in cima deL monte risposero eranno Contenti facendosse vn bata glione cō scaricare li squiopeti et abrasandosi lo capo cō li due re pigliassemo lisentia.

Dopo disnare tornassemo tucti in gioponne et andassemo insieme cō li duy Re neL mezo di in cima deL piu alto monte ɋ fosse Quando ariuassemo in cima Lo capo genneralle li disse como li era caro hauere sudato þ loro þ che esendo iui la croce nō poteua sinon grandamẽte Jouarli et domandoli qaL porto era migliore þ victuuaglie dicessero ɋ ne erano tre çioe Ceylon Zubu et calaghann ma che Zubu era piu grande et de meglior trafico et se profersenno di darni piloti ɋ ne insegniarebenno iL viago Lo capo gñale li rengratio et delibero de andarli þ ɋ cussi voleua la sua infelice sorte. posta la cruce ognuno dice vno pater noster et vna aue maria adorandola cosi li re fecenno poy descendessemo þ li sui campi Lauorattj et andassemo doue era lo balanghai li re feceno portare alquanti cochi açio se rinfrescassimo Lo capo li domando li piloti þ che la matina sequente voleua partirsi et ɋ li tratarebe como se medesimo Lasandoli vno de li nȓj þ ostagio risposero ɋ ogni ora li volesse eranno aL suo comādo ma nela nocte iL pimo re se mudo dopigniōe La matina quando eramo þ partirsi eL re mando adire aL capo generalle ɋ per amore suo aspectasse duj giornj fin ɋ facesse coglire el rizo et alti sui menuti pregandolo mandasse alguni homini þ ajutareli açio piu presto se spazasse ɋ luy medesimo voleua essere lo nȓo piloto. lo Capo mandoli alguni homini ma li Re tanto mangiorono et beueteno ɋ dormiteno tuto il giorno alguni þ escusarli dicero ɋ haueuano vno pocho de malle þ qeL giorno li nosti nō fecero niente ma neli alti dui seguenti lauorono.

|

|

About seventy leguas on the above course, and lying in twelve degrees of latitude and 146 in longitude, we discovered on Wednesday, March 6, a small island to the northwest, and two others toward the southwest, one of which was higher and larger than the other two. The captain-general wished to stop at the large island and get some fresh food, but he was unable to do so because the inhabitants of that island entered the ships and stole whatever they could lay their hands on, so that we could not protect ourselves. The men were about to strike the sails so that we could go ashore, but the natives very deftly stole from us the small boat that was fastened to the poop of the flagship. Thereupon, the captain-general in wrath went ashore with forty armed men, who burned some forty or fifty houses together with many boats, and killed seven men. He recovered the small boat, and we departed immediately pursuing the same course. Before we landed, some of our sick men begged us if we should kill any man or woman to bring the entrails to them, as they would recover immediately.

When we wounded any of those people with our crossbow-shafts, which passed completely through their loins from one side to the other, they, looking at it, pulled on the shaft now on this and now on that side, and then drew it out, with great astonishment, and so died. Others who were wounded in the breast did the same, which moved us to great compassion. Those people seeing us departing followed us with more than one hundred boats for more than one legua. They approached the ships showing us fish, feigning that they would give them to us; but then threw stones at us and fled. And although the ships were under full sail, they passed between them and the small boats [fastened astern], very adroitly in those small boats of theirs. We saw some women in their boats who were crying out and tearing their hair, for love, I believe, of those whom we had killed.

Each one of those people lives according to his own will, for they have no seignior. They go naked, and some are bearded and have black hair that reaches to the waist. They wear small palmleaf hats, as do the Albanians. They are as tall as we, and well built. They have no worship. They are tawny, but are born white. Their teeth are red and black, for they think that is most beautiful. The women go naked except that they wear a narrow strip of bark as thin as paper, which grows between the tree and the bark of the palm, before their privies. They are goodlooking and delicately formed, and lighter complexioned than the men; and wear their hair which is exceedingly black, loose and hanging quite down to the ground. The women do not work in the fields but stay in the house, weaving mats, baskets [casse: literally boxes], and other things needed in their houses, from palm leaves. They eat cocoanuts, camotes [batate], birds, figs one palmo in length [i.e., bananas], sugarcane, and flying fish, besides other things. They anoint the body and the hair with cocoanut and beneseed oil. Their houses are all built of wood covered with planks and thatched with leaves of the fig-tree [i.e., banana-tree] two brazas long; and they have floors and windows. The rooms and the beds are all furnished with the most beautiful palmleaf mats. They sleep on palm straw which is very soft and fine. They use no weapons, except a kind of a spear pointed with a fishbone at the end. Those people are poor, but ingenious and very thievish, on account of which we called those three islands the islands of Ladroni [i.e., of thieves]. Their amusement, men and women, is to plough the seas with those small boats of theirs. Those boats resemble fucelere, but are narrower, and some are black, [some] white, and others red. At the side opposite the sail, they have a large piece of wood pointed at the top, with poles laid across it and resting on the water, in order that the boats may sail more safely. The sail is made from palmleaves sewn together and is shaped like a lateen sail. For rudders they use a certain blade resembling a hearth shovel which have a piece of wood at the end. They can change stern and bow at will [literally: they make the stern, bow, and the bow, stern], and those boats resemble the dolphins which leap in the water from wave to wave. Those Ladroni [i.e., robbers] thought, according to the signs which they made, that there were no other people in the world but themselves.

At dawn on Saturday, March sixteen, 1521, we came upon a high land at a distance of three hundred leguas from the islands of Latroni – an island named Zamal [i.e., Samar]. The following day, the captain-general desired to land on another island which was uninhabited and lay to the right of the abovementioned island, in order to be more secure, and to get water and have some rest. He had two tents set up on the shore for the sick and had a sow killed for them. On Monday afternoon, March 18, we saw a boat coming toward us with nine men in it. Therefore, the captain-general ordered that no one should move or say a word without his permission. When those men reached the shore, their chief went immediately to the captain-general, giving signs of joy because of our arrival. Five of the most ornately adorned of them remained with us, while the rest went to get some others who were fishing, and so they all came. The captain-general seeing that they were reasonable men, ordered food to be set before them, and gave them red caps, mirrors, combs, bells, ivory, bocasine, and other things. When they saw the captain's courtesy, they presented fish, a jar of palm wine, which they call uraca [i.e., arrack], figs more than one palmo long [i.e., bananas], and others which were smaller and more delicate, and two cocoanuts. They had nothing else then, but made us signs with their hands that they would bring umay or rice, and cocoanuts and many other articles of food within four days.

Cocoanuts are the fruit of the palmtree. Just as we have bread, wine, oil, and milk, so those people get everything from that tree. They get wine in the following manner. They bore a hole into the heart of the said palm at the top called palmito [i.e., stalk], from which distils a liquor which resembles white must. That liquor is sweet but somewhat tart, and [is gathered] in canes [of bamboo] as thick as the leg and thicker. They fasten the bamboo to the tree at evening for the morning, and in the morning for the evening. That palm bears a fruit, namely, the cocoanut, which is as large as the head or thereabouts. Its outside husk is green and thicker than two fingers. Certain filaments are found in that husk, whence is made cord for binding together their boats. Under that husk there is a hard shell, much thicker than the shell of the walnut, which they burn and make therefrom a powder that is useful to them. Under that shell there is a white marrowy substance one finger in thickness, which they eat fresh with meat and fish as we do bread; and it has a taste resembling the almond. It could be dried and made into bread. There is a clear, sweet water in the middle of that marrowy substance which is very refreshing. When that water stands for a while after having been collected, it congeals and becomes like an apple. When the natives wish to make oil, they take that cocoanut, and allow the marrowy substance and the water to putrefy. Then they boil it and it becomes oil like butter. When they wish to make vinegar, they allow only the water to putrefy, and then place it in the sun, and a vinegar results like [that made from] white wine. Milk can also be made from it for we made some. We scraped that marrowy substance and then mixed the scrapings with its own water which we strained through a cloth, and so obtained milk like goat's milk. Those palms resemble date-palms, but although not smooth they are less knotty than the latter. A family of x persons can be supported on two trees, by utilizing them week about for the wine; for if they did otherwise, the trees would dry up. They last a century.

Those people became very familiar with us. They told us many things, their names and those of some of the islands that could be seen from that place. Their own island was called Zuluan and it is not very large. We took great pleasure with them, for they were very pleasant and conversable. In order to show them greater honor, the captain-general took them to his ship and showed them all his merchandise – cloves, cinnamon, pepper, ginger, nutmeg, mace, gold, and all the things in the ship. He had some mortars fired for them, whereat they exhibited great fear, and tried to jump out of the ship. They made signs to us that the abovesaid articles grew in that place where we were going. When they were about to retire they took their leave very gracefully and neatly, saying that they would return according to their promise. The island where we were is called Humunu; but inasmuch as we found two springs there of the clearest water, we called it Acquada da li buoni Segnialli [i.e., «the Watering-place of good Signs»], for there were the first signs of gold which we found in those districts. We found a great quantity of white coral there, and large trees with fruit a trifle smaller than the almond and resembling pine seeds. There are also many palms, some of them good and others bad. There are many islands in that district, and therefore we called them the archipelago of San Lazaro, as they were discovered on the Sabbath of St. Lazurus. They lie in x degrees of latitude toward the Arctic Pole, and in a longitude of one hundred and sixty-one degrees from the line of demarcation.

At noon on Friday, March 22, those men came as they had promised us in two boats with cocoanuts, sweet oranges, a jar of palm-wine, and a cock, in order to show us that there were fowls in that district. They exhibited great signs of pleasure at seeing us. We purchased all those articles from them. Their seignior was an old man who was painted [i.e., tattooed]. He wore two gold earrings [schione] in his ears, and the others many gold armlets on their arms and kerchiefs about their heads. We stayed there one week, and during that time our captain went ashore daily to visit the sick, and every morning gave them cocoanut water from his own hand, which comforted them greatly. There are people living near that island who have holes in their ears so large that they can pass their arms through them. Those people are caphri, that is to say, heathen. They go naked, with a cloth woven from the bark of a tree about their privies, except some of the chiefs who wear cotton cloth embroidered with silk at the ends by means of a needle. They are dark, fat, and painted. They anoint themselves with cocoanut and with beneseed oil, as a protection against sun and wind. They have very black hair that falls to the waist, and use daggers, knives, and spears ornamented with gold, large shields, fascines, javelins, and fishing nets that resemble rizali; and their boats are like ours.

On the afternoon of holy Monday, the day of our Lady, March twenty-five, while we were on the point of weighing anchor, I went to the side of the ship to fish, and putting my feet upon a yard leading down into the storeroom, they slipped, for it was rainy, and consequently I fell into the sea, so that no one saw me. When I was all but under, my left hand happened to catch hold of the clew-garnet of the mainsail, which was dangling [ascosa] in the water. I held on tightly, and began to cry out so lustily that I was rescued by the small boat. I was aided, not, I believe, indeed, through my merits, but through the mercy of that font of charity [i.e., of the Virgin]. That same day we shaped our course toward the west southwest between four small islands, namely, Cenalo, Hiunanghan, Ibusson, and Abarien.

On Thursday morning, March twenty-eight, as we had seen a fire on an island the night before, we anchored near it. We saw a small boat which the natives call boloto with eight men in it, approaching the flagship. A slave belonging to the captain-general, who was a native of Zamatra [i.e., Sumatra], which was formerly called Traprobana, spoke to them. They immediately understood him, came alongside the ship, unwilling to enter but taking a position at some little distance. The captain seeing that they would not trust us, threw them out a red cap and other things tied to a bit of wood. They received them very gladly, and went away quickly to advise their king. About two hours later we saw two balanghai coming. They are large boats and are so called [by those people]. They were full of men, and their king was in the larger of them, being seated under an awning of mats. When the king came near the flagship, the slave spoke to him. The king understood him, for in those districts the kings know more languages than the other people. He ordered some of his men to enter the ships, but he always remained in his balanghai, at some little distance from the ship until his own men returned; and as soon as they returned he departed. The captain-general showed great honor to the men who entered the ship, and gave them some presents, for which the king wished before his departure to give the captain a large bar of gold and a basketful of ginger. The latter, however, thanked the king heartily but would not accept it. In the afternoon we went in the ships [and anchored] near the dwellings of the king.

Next day, holy Friday, the captain-general sent his slave, who acted as our interpreter, ashore in a small boat to ask the king if he had any food to have it carried to the ships; and to say that they would be well satisfied with us, for he [and his men] had come to the island as friends and not as enemies. The king came with six or eight men in the same boat and entered the ship. He embraced the captain-general to whom he gave three porcelain jars covered with leaves and full of raw rice, two very large orade, and other things. The captain-general gave the king a garment of red and yellow cloth made in the Turkish fashion, and a fine red cap; and to the others (the king's men), to some knives and to others mirrors. Then the captain-general had a collation spread for them, and had the king told through the slave that he desired to be casi casi with him, that is to say, brother. The king replied that he also wished to enter the same relations with the captain-general. Then the captain showed him cloth of various colors, linen, coral [ornaments], and many other articles of merchandise, and all the artillery, some of which he had discharged for him, whereat the natives were greatly frightened. Then the captain-general had a man armed as a soldier, and placed him in the midst of three men armed with swords and daggers, who struck him on all parts of the body. Thereby was the king rendered almost speechless. The captain-general told him through the slave that one of those armed men was worth one hundred of his own men. The king answered that that was a fact. The captain-general said that he had two hundred men in each ship who were armed in that manner. He showed the king cuirasses, swords, and bucklers, and had a review made for him. Then he led the king to the deck of the ship, that is located above at the stern; and had his sea-chart and compass brought. He told the king through the interpreter how he had found the strait in order to voyage thither, and how many moons he had been without seeing land, whereat the king was astonished. Lastly, he told the king that he would like, if it were pleasing to him, to send two of his men with him so that he might show them some of his things. The king replied that he was agreeable, and I went in company with one of the other men.

When I reached shore, the king raised his hands toward the sky and then turned toward us two. We did the same toward him as did all the others. The king took me by the hand; one of his chiefs took my companion; and thus they led us under a bamboo covering, where there was a balanghai, as long as eighty of my palm lengths, and resembling a fusta. We sat down upon the stern of that balanghai, constantly conversing with signs. The king's men stood about us in a circle with swords, daggers, spears, and bucklers. The king had a plate of pork brought in and a large jar filled with wine. At every mouthful, we drank a cup of wine. The wine that was left [in the cup] at any time, although that happened but rarely, was put into a jar by itself. The king's cup was always kept covered and no one else drank from it but he and I. Before the king took the cup to drink, he raised his clasped hands toward the sky, and then toward me; and when he was about to drink, he extended the fist of his left hand toward me (at first I thought that he was about to strike me) and then drank. I did the same toward the king. They all make those signs one toward another when they drink. We ate with such ceremonies and with other signs of friendship. I ate meat on holy Friday, for I could not help myself. Before the supper hour I gave the king many things which I had brought. I wrote down the names of many things in their language. When the king and the others saw me writing, and when I told them their words, they were all astonished. While engaged in that the supper hour was announced. Two large porcelain dishes were brought in, one full of rice and the other of pork with its gravy. We ate with the same signs and ceremonies, after which we went to the palace of the king which was built like a hayloft and was thatched with fig [i.e., banana] and palm leaves. It was built up high from the ground on huge posts of wood and it was necessary to ascend to it by means of ladders. The king made us sit down there on a bamboo mat with our feet drawn up like tailors. After a half-hour a platter of roast fish cut in pieces was brought in, and ginger freshly gathered, and wine. The king's eldest son, who was the prince, came over to us, whereupon the king told him to sit down near us, and he accordingly did so. Then two platters were brought in (one with fish and its sauce, and the other with rice), so that we might eat with the prince. My companion became intoxicated as a consequence of so much drinking and eating. They used the gum of a tree called anime wrapped in palm or fig [i.e., banana] leaves for lights. The king made us a sign that he was going to go to sleep. He left the prince with us, and we slept with the latter on a bamboo mat with pillows made of leaves. When day dawned the king came and took me by the hand, and in that manner we went to where we had had supper, in order to partake of refreshments, but the boat came to get us. Before we left, the king kissed our hands with great joy, and we his. One of his brothers, the king of another island, and three men came with us. The captain-general kept him to dine with us, and gave him many things.

Pieces of gold, of the size of walnuts and eggs are found by sifting the earth in the island of that king who came to our ships. All the dishes of that king are of gold and also some portion of his house, as we were told by that king himself. According to their customs he was very grandly decked out [molto in ordine], and the finest looking man that we saw among those people. His hair was exceedingly black, and hung to his shoulders. He had a covering of silk oh his head, and wore two large golden earrings fastened in his ears. He wore a cotton cloth all embroidered with silk, which covered him from the waist to the knees. At his side hung a dagger, the haft of which was somewhat long and all of gold, and its scabbard of carved wood. He had three spots of gold on every tooth, and his teeth appeared as if bound with gold. He was perfumed with storax and benzoin. He was tawny and painted [i.e., tattooed] all over. That island of his was called Butuan and Calagan. When those kings wished to see one another, they both went to hunt in that island where we were. The name of the first king is Raia Colambu, and the second Raia Siaui.

Early on the morning of Sunday, the last of March, and Easter-day, the captain-general sent the priest with some men to prepare the place where mass was to be said; together with the interpreter to tell the king that we were not going to land in order to dine with him, but to say mass. Therefore the king sent us two swine that he had had killed. When the hour for mass arrived, we landed with about fifty men, without our body armor, but carrying our other arms, and dressed in our best clothes. Before we reached the shore with our boats, six pieces were discharged as a sign of peace. We landed; the two kings embraced the captain-general, and placed him between them. We went in marching order to the place consecrated, which was not far from the shore. Before the commencement of mass, the captain sprinkled the entire bodies of the two kings with musk water.» The mass was offered up. The kings went forward to kiss the cross as we did, but they did not offer the sacrifice. When the body of our Lord was elevated, they remained on their knees and worshiped Him with clasped hands. The ships fired all their artillery at once when the body of Christ was elevated, the signal having been given from the shore with muskets. After the conclusion of mass, some of our men took communion. The captain-general arranged a fencing tournament, at which the kings were greatly pleased. Then he had a cross carried in and the nails and a crown, to which immediate reverence was made. He told the kings through the interpreter that they were the standards given to him by the emperor his sovereign, so that wherever he might go he might set up those his tokens. [He said] that he wished to set it up in that place for their benefit, for whenever any of our ships came, they would know that we had been there by that cross, and would do nothing to displease them or harm their property [property: doublet in original MS.]. If any of their men were captured, they would be set free immediately on that sign being shown. It was necessary to set that cross on the summit of the highest mountain, so that on seeing it every morning, they might adore it; and if they did that, neither thunder, lightning, nor storms would harm them in the least. They thanked him heartily and [said] that they would do everything willingly. The captain-general also had them asked whether they were Moros or heathen, or what was their belief. They replied that they worshiped nothing, but that they raised their clasped hands and their face to the sky; and that they called their god «Abba.» Thereat the captain was very glad, and seeing that, the first king raised his hands to the sky, and said that he wished that it were possible for him to make the captain see his love for him. The interpreter asked the king why there was so little to eat there. The latter replied that he did not live in that place except when he went hunting and to see his brother, but that he lived in another island where all his family were. The captain-general had him asked to declare whether he had any enemies, so that he might go with his ships to destroy them and to render them obedient to him. The king thanked him and said that he did indeed have two islands hostile to him, but that it was not then the season to go there. The captain told him that if God would again allow him to return to those districts, he would bring so many men that he would make the king's enemies subject to him by force. He said that he was about to go to dinner, and that he would return afterward to have the cross set up on the summit of the mountain. They replied that they were satisfied, and then forming in battalion and firing the muskets, and the captain having embraced the two kings, we took our leave.

After dinner we all returned clad in our doublets, and that afternoon went together with the two kings to the summit of the highest mountain there. When we reached the summit, the captain-general told them that he esteemed highly having sweated for them, for since the cross was there, it could not but be of great use to them. On asking them which port was the best to get food, they replied that there were three, namely, Ceylon, Zubu, and Calaghann, but that Zubu was the largest and the one with most trade. They offered of their own accord to give us pilots to show us the way. The captain-general thanked them, and determined to go there, for so did his unhappy fate will. After the cross was erected in position, each of us repeated a Pater Noster and an Ave Maria, and adored the cross; and the kings did the same. Then we descended through their cultivated fields, and went to the place where the balanghai was. The kings had some cocoanuts brought in so that we might refresh ourselves. The captain asked the kings for the pilots for he intended to depart the following morning, and [said] that he would treat them as if they were the kings themselves, and would leave one of us as hostage. The kings replied that every hour he wished the pilots were at his command, but that night the first king changed his mind, and in the morning when we were about to depart, sent word to the captain-general, asking him for love of him to wait two days until he should have his rice harvested, and other trifles attended to. He asked the captain-general to send him some men to help him, so that it might be done sooner; and said that he intended to act as our pilot himself. The captain sent him some men, but the kings ate and drank so much that they slept all the day. Some said to excuse them that they were slightly sick. Our men did nothing on that day, but they worked the next two days.

|

Biblioteca ambrosiana di Milano, Ms. L 103 Sup., fol. 16v

Biblioteca ambrosiana di Milano, Ms. L 103 Sup., fol. 18v

|